BAMIDBAR

I. Summary

A. A Census Is Taken. During the second year after the Exodus, Hashem commanded Moshe and Aaron to conduct a census of male Israelites ages 20-60 (i.e., who were liable for military service). The census revealed 603,550 such men (Levites were excluded because of their special duties in connection with the Mishkon (Tabernacle)).

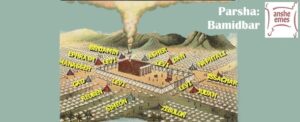

B. The Encampment. The camp was arranged in a quadrilateral, with the Mishkon in the center, and protected on all four sides by the tents of the Levi’im. The twelve tribes were divided into four groups, each bearing the name of the leading tribe, around the perimeter.

C. The Duties of the Levites. Originally, Hashem selected the first-borns to perform His holy services; however, following the Golden Calf, this coveted task was entrusted solely to the Levi’im (who had remained faithful to Hashem). Therefore, Hashem commanded Moshe to appoint the Levi’im (who then numbered 22,300) to Mishkon service under the supervision of Aaron and his sons. Each of the three Levite families were assigned separate tasks: (a) the Gershonites were responsible for transporting the Mishkon coverings; (b) the Kohathites were to carry the Ark, the Shulhan (Table), Menorah and Altars (and were warned not to touch or even look upon these sacred objects, which were covered by Aaron and his sons prior to being moved); and (c) the Merarites were entrusted with transporting the boards, pillars, bolts and sockets. Aaron’s son, Elazar, was the general supervisor of the Mishkon, watching in particular over the oil, incense, Mincha offering and anointing oil.

II. Divrei Torah

A. LilMode U’lilamed (Rabbi Mordechai Katz)

1. The humility of the desert. This Parsha (and the entire fourth book of the Torah) is entitled “Bamidbar” (desert) since Hashem promulgated His laws to the Jews in the desert. The desert impresses upon us the importance of humility — just as the desert consists only of sand, we are composed merely of dust. However, just as the desert was transformed into a holy spot by the appearance of the Divine Presence, so too can man become a source of greatness if he allows his spiritual spark to dominate his actions.

2. Yissachar and Zevulun. Why does the Parsha conjoin the list of all of the tribes’ names with an “and”, except for the names of Yissachar and Zevulun? Because of their unique relationship — Yissachar were outstanding Torah scholars, who often lacked sufficient time to earn a living to support themselves and their families; Zevulun were successful merchants, who used their wealth to support Yissachar’s Torah study. Each of their efforts were indispensable to the others’ and their reward is the same. Rabbi Chaim Shmuelevitz commented that just as those who support Torah study financially have the merit of the Torah study of those they support, so too does anyone who influences another to study Torah share in that person’s merit.

B. Growth Through Torah (Rabbi Zelig Pliskin)

1. Humility enables you to learn from everyone and teach everyone. As noted above, the desert symbolizes humility. As the Midrash teaches, “whoever does not make himself open and free like a wilderness will not be able to acquire wisdom and Torah.” This, comments Matnos Kehunah, refers to being humble enough to learn from, and teach, everyone.

2. Make your descendants proud of you. “And you shall be one man from each tribe, each man should be the head of his family.” Rabbi Moshe Chaifetz says that this teaches us that we each should be the head of our family’s lineage — rather than boasting about our prominent lineage, we should be an elevated person in our own right and someone whom our descendants are proud to consider their ancestor.

C. Kol Dodi on the Torah (Rabbi Dovid Feinstein)

The importance of each individual. “Count the heads of all the congregation of the Children of Israel . . . ” The reference to “count the heads” literally means “raise the heads”, highlighting the fundamental importance that Judaism attaches to each individual (not only a member of the Jewish people, but as an individual as well). (Ramban notes that this also suggests that, if the Jews are worthy, they will be uplifted.)

D. Majesty of Man (Rabbi A. Henach Leibowitz)

The Value of each Jew. As noted above, the census underscores each Jew’s value. Ramban further explains that Hashem’s command to Moshe to count the “number of the names” means that he was to count each Jew with honor and dignity (i.e., rather than simply asking the head of each household for a “head-count”, each person was to pass before Moshe with honor). When dealing with others, we must remember that every person is unique and valuable and, as the Talmud teaches, worthy of the entire world existing for his/her sake.

E. Artscroll Chumash

The role of the Tabernacle. The Book of Bamidbar deals in great measure with the laws and history of the Tabernacle. Ramban notes that the striking parallels between the Tabernacle and the Revelation at Sinai suggest that the Tabernacle (and later the Holy Temple and now the synagogue) was to serve as a permanent substitute for the Heavenly Presence that rested upon Israel at Sinai. By making the Tabernacle (and the Temple and later the synagogue) central to the nation (not only geographically, but conceptually), the Jews would (and will) always keep “Mount Sinai” among themselves.

F. In The Garden Of The Torah (the Lubavitcher Rebbe, Rabbi Menachem M. Schneerson, z’tl)

The meaning of the desert. In communication, the choice of setting is very important. What does the choice of the desert teach us?

1. The Torah belongs to each Jew. Like the desert, the Torah doesn’t belong to any particular individual. (As Sifri states “the crown of the Torah is set aside, waiting, and ready for every Jew . . . whoever desires, may come and take it”.)

2. We must remove the constraints holding back our commitment to Torah. As our Sages teach, a person must “make himself like a desert, relinquishing all concerns” (i.e., he must remove the constraints which hold back his commitment to Torah). Thus, in order to approach Torah, we must step beyond ourselves and accept a different framework of understanding. (This is exemplified by our ancestors’ pledge: “We will do and [then] we will listen”.)

3. Torah transcends ordinary existence. The revelation of the Torah was too great to be confined within ordinary existence.

4. A declaration of dependence. In the desert, the Jews depended on Hashem, not natural resources, for their existence. Despite its barrenness and desolation, our ancestors entered the desert with loving trust, for which Hashem responded with loving care (providing them with food, clothing and all of their other needs, thereby allowing them to devote themselves to Torah). While today we have “natural” means of deriving our own livelihood, nature itself is still a series of miracles (unfortunately, because of their constant reoccurrence, we no longer see these miracles as special). But, we must use each “reoccurrence” as a reminder that we still rely on Hashem, giving precedence to the Torah rather than our material concerns.

5. The opportunity for a spiritual connection to Hashem. Although a person may feel empty and desolate — living in a spiritual desert — there is no need to despair. Hashem descended into the desert to give the Torah; the same is true today — regardless of one’s spiritual level, Hashem offers the opportunity of establishing a connection through the medium of the Torah.

6. Preparation for Shavuos. Parsha Bamidbar is always read before Shavuos. The Jewish holidays do not merely commemorate past events, but also provide us with an opportunity to relive them. To relive the Sinai experience, we must first pass though the “desert” and its lessons — at least in a spiritual sense.

G. Reflections on the Sedra (Rabbi Zalman Posner)

The pricelessness of each individual. Counting implies value. The Torah counts Israel to the last person, because each one is priceless. Rashi makes a noteworthy observation. He cites several examples of counting Israel, specifically that following the Golden Calf and in this week’s Parsha, following the dedication of the Sanctuary. These examples are in striking contrast — one depicts Israel in the depths of idolatry; the other represents Israel in a moment of dedication to G-d’s service. Perhaps Rashi meant to indicate that the value of each person is intrinsic, that each soul has an innate purity beyond sullying. Each individual is unique and priceless, not only in moments of consecration, but even when fallible and fallen.

H. Peninim on the Torah (Rabbi A.L. Scheinbaum)

A lesson for parents. HaRav Moshe Swift, z’tl notes a disparity between the census of the Israel and that of the Levites. The former were countered from age 20 and older, thereby facilitating an easy count. The latter were counted from age one month and upwards, which demanded a more difficult count. The Midrash emphasizes this by noting that Moshe asked, “How can I enter their tents to determine the number of babies in each family?,” to which Hashem responded, “You do your share and I will do mine.” The Midrash continues that Moshe stood at the doorway of each tent and the Shechinah (Divine Presence) preceded him and a Divine voice emanated from each tent stating the number of babies therein. This is the hidden meaning of this verse — Hashem’s Word facilitated Moshe’s census. There is a profound lesson here: in order for Moshe to count the children outside of the house, the Divine Presence must first have penetrated inside the house. If Jewish children are be “counted” as proud members of the Jewish people, the Divine Presence — through prayer, Shabbos, Holidays, kashrus, Torah study, charity, etc. — must have penetrated the house during their upbringing.

I. Living Each Week (Rabbi Abraham Twerski)

1. The role of the teacher. “And these are the generations of Aaron and Moshe . . . and these are the names of the sons of Aaron.” Although the Torah states that these are the generations of Aaron and Moshe, it lists only Aaron’s children. This teaches us that one who teaches another’s children Torah is also deemed to be his/her “father”.

2. When the task appears impossible. As noted above, the census of the Levites demanded Divine assistance. One might ask that since the census was dependent upon Divine revelation, why was there a need for Moshe to do anything at all? Why didn’t G-d simply tell Moshe how many Levites there were? The answer to this question is essentially the formula for man’s actions in this world. An omnipotent G-d could do everything and is hardly in need of human acts to accomplish anything. For reasons known only to G-d, man was placed on this earth with a mission that only he can achieve, and it is his responsibility to fulfill that mission. If the fulfillment of that mission appears to be beyond the scope of man’s capabilities, this does not exempt him from doing his utmost to reach this goal. Man must do whatever he can, and whatever is truly beyond him become G-d’s responsibility. As Pirke Avos states, “it is not up to you to complete the task, yet you are not free to desist form it.” We today, as Moshe then, must not retreat from any mitzvah even if its fulfillment appears beyond our means. We must which we can, and leave the rest to G-d.

3. Impact of Shabbos. “As they rest, so shall they move.” While the literal meaning of this verse is that the tribes of Israel were to travel in the same formation as they camped, this verse also lends itself to another interpretation. Our lives can be divided into: (a) the work week; and (b) Shabbos, the day of rest. Shabbos, the “day of rest” is not merely a day to recuperate from the work week; rather, it is day of spirituality (or, as the Zohar terms it, “the day of the soul”). While oneg Shabbos (enjoying the Shabbos) is indeed a mitzvah and we are required to honor Shabbos with nice clothing and good food, this is not the totality of Shabbos. It is also be a day of “soul,” a day in which we are to utilize its precious moments in prayer, Torah study and other means of connecting to Hashem. If one reflects on the words of the Kiddush — the declaration that G-d created the universe — then one may reflect on the purpose of his/her own existence and dedicate his/herself to achieving that purpose. Used in this manner, Shabbos has the potential to positively impact what we do and how we act even on the weekdays.

J. Something To Say (Rabbi Dovid Goldwasser)

1. Striving to Acquire Torah. The Midrash tells us that the Torah was given to Israel is fire, water and in a wilderness. The Shem MiShmuel comments that these three elements symbolize the way in which we should strive to acquire Torah: we should learn it with the “fire” of enthusiasm – with an eager and fervent heart. We also need water – a calm and thoughtful approach to learning, symbolized by the tranquility of water. Finally, we need the “wilderness” – a willingness to forego material pursuits that serve as obstacles to spiritual accomplishments. After World War II, when the Buchenwald concentration camp was liberated, announcements went out over the loudspeaker that Shabbos services were going to be held in one of the large rooms. A survivor, curious who would attend, went to the service. When he arrived, he was amazed to see that an enormous crowd had gathered to show their unwavering faith in G-d. Indeed, our ancestors were willing to go through fire, water and wilderness, every necessary way in their eagerness to observe the Torah.

2. A Constant Census. “Take a census of the entire assembly of the Children of Israel.” Rashi comments: “Out of G-d’s love for B’nei Yisroel, He counts them at all times.” Rabbi Yechezkel of Kuzmir asks, “does G-d count B’nei Yisroel at every moment? And how can He count B’nei Yisroel as if they are all equal? Chazal teach that there is no person without his/her time; meaning that each of us has a charmed time in life, a moment of glory. This is what Rashi meant – that G-d counts us according to the best times of our lives, and in that way we are all beloved to Him.

3. The Preciousness Of Each Soul. . “Take a census of the entire assembly of the Children of Israel, according to their families, according to their fathers’ households, by number of the names.” While the Jews were traveling in the desert on the way to Israel, G-d commanded Moshe and Aaron to take a census. The Sages asks why the Torah adds the phrase “the number of the names”. In taking a census, isn’t it sufficient to only count the number of people? What is the significance of the names? When we count members of the Jewish nation, we don’t merely ascribe them a number; each one is a vital being with his/her own “name,” a precious and holy member of the community. A great Tzaddik was once standing to accept a long line of Hassidim who were passing by to give him greeting. After standing for several hours, someone asked him, “Rebbe, how can you stand for such a long time?” He replied, “Tiring? One does not get tired of counting diamonds.”

K. Reflections on the Sedra (Rabbi Zalmon Posner)

A Constant Census. Rashi contrasts the census in this Parsha with the census that followed the Golden Calf. This census represents Israel in a moment of dedication to service of G-d, whereas the latter represents Israel in the depths of idolatry. Rashi contrasts these two instances to indicate that our worth is intrinsic, that our souls have an innate purity which cannot be sullied. Each of us is unique and priceless, not only in moments of consecration, but even when fallible and fallen.

L. Growth Through Torah (Rabbi Zelig Pliskin)

1. Keep Away From Listening to Lashon Hara. “But you shall not number the tribe of Levi, nor take the sum of them among the Children of Israel.” Rashi cites the Midrash that one of the reasons why the Tribe of Levi was not counted was that G-d foresaw that everyone over 20 years of age would die in the 40 years the Israelites were in the wilderness. Therefore He said, “The Levites should not be counted among the others in order not to be included with them. They are Mine since they did not transgress in the sin of the Golden Calf.” However, the decree of dying in the wilderness was for the transgression of accepting the spies’ negative report. Rashi should have said that the Levites did not transgress in the sins of the spies, rather than they did not transgress the Golden Calf. The answer, wrote the Sifsai Chachomim, is that the Levites also accepted the negative report of the spies. But, the decree of dying in the wilderness was because of the double transgressions of the Golden Calf and the spies. Since the Levites were not guilty in the former, they were not included in the decree. Rabbi Baruch Sorotzkin commented that we see from here the dangers of listening to loshon hara, a negative report about others. Even though the Levites had the strength of character not to sin when others did with the Golden Calf, they still fell prey to accepting the lashon hara about the land of Israel. From here we should lean how far we need to keep from listening to lashon hara.

2. Influence Others To Study Torah. “The Tribe of Zevulun . . . ” Baal Haturim notes that in reference to certain of the tribes that were together with the other tribes, the Torah adds the letter “vav” – which denotes that they are separate but together. But, as regards the tribe of Zevulun, there is not a “vav.” This is because the tribe of Yissochar, which is mentioned right above, devoted themselves to Torah study, while the tribe of Zevulun worked to support both of them. Because they enabled the tribe of Yissochar to study Torah, they are considered as one tribe and their reward is the same. Rabbi Chaim Shmuelevitz used to comment that just as those who support Torah study financially have the merit of Torah study of those they support, so too anyone who influences another person to study Torah shares in the merit of that person.

3. Respecting Others’ Privacy. “And Moshe commanded them according to the word of the Almighty, as He commanded.” Rashi cites the Midrash that since the Levites were counted from the age of 30 days, Moshe asked G-d, “How can I enter the private tents of other people to know how many infants each family has?” G-d replied, “You do what is required of you, and I will take care of the rest.” Therefore, when Moshe walked in front of each tent, a Divine voice announced the number of occupants. Rabbi Chaim Shmuelevitz used to note the importance of observing the principles of derech eretz. Although Moshe had a mitzvah to count the people, he felt it wrong to invade their privacy. So too must we particularly careful in protecting others’ privacy.

M. Living Each Week (Rabbi Abraham Twerski)

Humility and Self-Esteem. “G-d spoke to Moshe in the wilderness of Sinai. . . . count the heads of the entire congregation of the Children of Israel . . . ” The literal translation of the “count the heads” is “elevate the heads.” The Talmud states that the choice of the wilderness as the site for the giving of the Torah was symbolic, to teach us that only if a person effaces himself, rids himself of vanity, and divests himself of all preconceptions — thus considering himself barren as the wilderness – is he capable of receiving the Divine word. (Nedarim 55a). Humility is considered the fundamental trait for character development. We must, however, be cautious not to confuse humility with feelings of inadequacy or inferiority. Thus, the words “elevate the head” – each of us should know that we are capable of being elevated, of achieving the greatest heights.

N. Rabbi Frand on The Parsha

Not Enough Respect. “Nadav and Avihu died . . . and they had no children.” Nadav and Avihu, Aaron’s sons, dies supernatural and mysterious deaths. The Torah tells us (Vayikra 10:1-2) that they brought a “strange fire” into the Mishkan, and that a fire snaked out from the Holy of Holies and snuffed out their lives. Why did they die? There are different opinions among the Sages. The common denominator among these opinions is that they lacked a certain level of respect. In this Parsha, however, we encounter an entirely different approach. “Nadav and Avihu died, and they had no children.” The Talmud (Yevamos 64a) infers from here that whoever does not make the effort to have children deserves to die. This seems to indicate that Nadav and Avihu died because they did not try to have children; it contradicts the opinions that they died because of intoxication, insubordination or other reasons. The Chasem Sofer suggests that there is no conflict whatsoever. The problem was Nadav and Avihu was indeed a deficiency in their demonstrating respect. Each of us has to grapple with this same issue. How can we measure the level of our own respectfulness? By our children. If our children are disrespectful to us, we can be sure that we are not sufficiently respectful to others. Rav Wolbe, in his Alei Shur, applies this concept to all areas of middos. “There is no greater factor in improving one’s middos,” he writes, “than having children.” We have a tendency to overlook our own flaw, yet can see the flaws of our children all too readily. If we only realize the truism that we are the source of our children’s flaws, we will make every effort to correct the situation. This is what the Sages may have meant when they said that Nadav and Avihu died because they did not have children. Had they had children, they would have noticed any lack of respect in their behavior and, in turn, would have improved themselves.

O. Tell It From the Torah

1. The Importance of a Learning Partner. “And G-d spoke to Moshe in the desert saying.” The Midrash notes that Torah was giving through fire, water and in the desert. The first two symbolize opposites, teaching us that Torah is best learned with a friend, who thinks in a different way than we do.

2. A Teacher/Father. “And these are the offspring of Aaron and Moshe . . . ” Why does the Torah treat Aaron’s children as if they belong to Moshe as well? The Talmud (Sanhedrin 9b) states that Moshe used to used Aaron’s children Torah. From here we learn that whoever teaches his friends’ children, it is as if he was involved in raising them himself.

P. Vedibarta Bam (Rabbi Moshe Bogomilsky)

1. The Torah Belongs To Each Of Us. Why did G-d give the Torah in the wilderness? The wilderness is essentially ownerless; no one has any particular claim to it. G-d was thus indicating that the Torah belong to everyone.

2. The Lessons Of Fire, Water and Wilderness. As noted above, the Midrash teaches that the Torah was given through three things: fire, water and the wilderness. What do these three things teach us?

(a) Fire teaches the Torah should be studied and practiced with warmth and vigor.

(b) Like fire rises upward, we must go from strength to strength, rising higher and higher in our observance of Torah.

(c) Water fulfills a physical need. However, unlike other physical needs, we have little desire to overindulge in it. Likewise, we should be satisfied with our material circumstances and indulge instead in the study of Torah.

(d) The wilderness is an abandoned property in which anyone may set forth. This teaches us that, in order to succeed in Torah study, we must permit all Jews to associate and study with us.

(e) Fire and water are opposites. Fire represents destruction, whereas water represents enrichment. G-d gave the Torah with fire and water to teach us that if a person is, G-d forbid, experiencing deprivation, he must study and observe Torah. On the other hand, someone blessed with affluence must also study Torah and live by its teachings.

(f) The wilderness reminds us that the Torah’s teachings are not limited to any specific location or context.

3. Enough Love For Each Of Us. “Take a census of the entire assembly of the Children of Israel.” Rashi comments that G-d always counts the Jewish people because of His love for them. What lesson can we learn from the counting of the Jewish people? When G-d instructed Moshe to count the Jews, He told him to count each Jew “as one” – no more and no less. The Jewish people are His people; each Jew is equally beloved and possesses a spark of G-dliness. Thus, irrespective of differences in observance levels, none should be overlooked or rejected.

Q. LilMode U’lilamed (Rabbi Mordechai Katz)

1. The humility of the desert. This Parsha (and the entire fourth book of the Torah) is entitled “Bamidbar” (desert) since Hashem promulgated His laws to the Jews in the desert. The desert impresses upon us the importance of humility — just as the desert consists only of sand, we are composed merely of dust. However, just as the desert was transformed into a holy spot by the appearance of the Divine Presence, so too can man become a source of greatness if he allows his spiritual spark to dominate his actions.

2. Yissachar and Zevulun. Why does the Parsha conjoin the list of all of the tribes’ names with an “and”, except for the names of Yissachar and Zevulun? Because of their unique relationship — Yissachar were outstanding Torah scholars, who often lacked sufficient time to earn a living to support themselves and their families; Zevulun were successful merchants, who used their wealth to support Yissachar’s Torah study. Each of their efforts were indispensable to the others’ and their reward is the same. Rabbi Chaim Shmuelevitz commented that just as those who support Torah study financially have the merit of the Torah study of those they support, so too does anyone who influences another to study Torah share in that person’s merit.

R. Growth Through Torah (Rabbi Zelig Pliskin)

1. Humility enables you to learn from everyone and teach everyone. As noted above, the desert symbolizes humility. As the Midrash teaches, “whoever does not make himself open and free like a wilderness will not be able to acquire wisdom and Torah.” This, comments Matnos Kehunah, refers to being humble enough to learn from, and teach, everyone.

2. Make your descendants proud of you. “And you shall be one man from each tribe, each man should be the head of his family.” Rabbi Moshe Chaifetz says that this teaches us that we each should be the head of our family’s lineage — rather than boasting about our prominent lineage, we should be an elevated person in our own right and someone whom our descendants are proud to consider their ancestor.

S. Kol Dodi on the Torah (Rabbi Dovid Feinstein)

The importance of each individual. “Count the heads of all the congregation of the Children of Israel . . . ” The reference to “count the heads” literally means “raise the heads”, highlighting the fundamental importance that Judaism attaches to each individual (not only a member of the Jewish people, but as an individual as well). (Ramban notes that this also suggests that, if the Jews are worthy, they will be uplifted.)

T. Majesty of Man (Rabbi A. Henach Leibowitz)

The Value of each Jew. As noted above, the census underscores each Jew’s value. Ramban further explains that Hashem’s command to Moshe to count the “number of the names” means that he was to count each Jew with honor and dignity (i.e., rather than simply asking the head of each household for a “head-count”, each person was to pass before Moshe with honor). When dealing with others, we must remember that every person is unique and valuable and, as the Talmud teaches, worthy of the entire world existing for his/her sake.

U. Artscroll Chumash

The role of the Tabernacle. The Book of Bamidbar deals in great measure with the laws and history of the Tabernacle. Ramban notes that the striking parallels between the Tabernacle and the Revelation at Sinai suggest that the Tabernacle (and later the Holy Temple and now the synagogue) was to serve as a permanent substitute for the Heavenly Presence that rested upon Israel at Sinai. By making the Tabernacle (and the Temple and later the synagogue) central to the nation (not only geographically, but conceptually), the Jews would (and will) always keep “Mount Sinai” among themselves.

V. In The Garden Of The Torah (the Lubavitcher Rebbe, Rabbi Menachem M. Schneerson, z’tl)

The meaning of the desert. In communication, the choice of setting is very important. What does the choice of the desert teach us?

1. The Torah belongs to each Jew. Like the desert, the Torah doesn’t belong to any particular individual. (As Sifri states “the crown of the Torah is set aside, waiting, and ready for every Jew . . . whoever desires, may come and take it”.)

2. We must remove the constraints holding back our commitment to Torah. As our Sages teach, a person must “make himself like a desert, relinquishing all concerns” (i.e., he must remove the constraints which hold back his commitment to Torah). Thus, in order to approach Torah, we must step beyond ourselves and accept a different framework of understanding. (This is exemplified by our ancestors’ pledge: “We will do and [then] we will listen”.)

3. Torah transcends ordinary existence. The revelation of the Torah was too great to be confined within ordinary existence.

4. A declaration of dependence. In the desert, the Jews depended on Hashem, not natural resources, for their existence. Despite its barrenness and desolation, our ancestors entered the desert with loving trust, for which Hashem responded with loving care (providing them with food, clothing and all of their other needs, thereby allowing them to devote themselves to Torah). While today we have “natural” means of deriving our own livelihood, nature itself is still a series of miracles (unfortunately, because of their constant reoccurrence, we no longer see these miracles as special). But, we must use each “reoccurrence” as a reminder that we still rely on Hashem, giving precedence to the Torah rather than our material concerns.

5. The opportunity for a spiritual connection to Hashem. Although a person may feel empty and desolate — living in a spiritual desert — there is no need to despair. Hashem descended into the desert to give the Torah; the same is true today — regardless of a person’s spiritual level, Hashem offers the opportunity of establishing a connection through the medium of the Torah.

6. Preparation for Shavuos. Parsha Bamidbar is always read before Shavuos. The Jewish holidays do not merely commemorate past events, but also provide us with an opportunity to relive them. To relive the Sinai experience, we must first pass though the “desert” and its lessons — at least in a spiritual sense.

W. Reflections on the Sedra (Rabbi Zalman Posner)

The pricelessness of each individual. Counting implies value. The Torah counts Israel to the last person, because each one is priceless. Rashi makes a noteworthy observation. He cites several examples of counting Israel, specifically that following the Golden Calf and in this week’s Parsha, following the dedication of the Sanctuary. These examples are in striking contrast — one depicts Israel in the depths of idolatry; the other represents Israel in a moment of dedication to G-d’s service. Perhaps Rashi meant to indicate that the value of each person is intrinsic, that each soul has an innate purity beyond sullying. Each individual is unique and priceless, not only in moments of consecration, but even when fallible and fallen.

X. Peninim on the Torah (Rabbi A.L. Scheinbaum)

A lesson for parents. HaRav Moshe Swift, z’tl notes a disparity between the census of the Israel and that of the Levites. The former were countered from the age 20 and older, thereby facilitating an easy count. The latter were counted from the age of one month upwards, which demanded a more difficult count. The Midrash emphasizes this by noting that Moshe asked, “How can I enter their tents to determine the number of babies in each family?,” to which Hashem responded, “You do your share and I will do mine.” The Midrash continues that Moshe stood at the doorway of each tent and the Shechinah (Divine Presence) preceded him and a Divine voice emanated from each tent stating the number of babies therein. This is the hidden meaning of this verse — Hashem’s Word facilitated Moshe’s census. There is a profound lesson here . . . in order for Moshe to count the children outside of the house, the Divine Presence must first have penetrated inside the house. If Jewish children are be “counted” as proud members of the Jewish people, the Divine Presence — through prayer, Shabbos, Holidays, kashrus, Torah study, charity, etc. — must have penetrated the house during their upbringing.

Y. Living Each Week (Rabbi Abraham Twerski)

1. The role of the teacher. “And these are the generations of Aaron and Moshe . . . and these are the names of the sons of Aaron.” Although the Torah states that these are the generations of Aaron and Moshe, it lists only Aaron’s children. This teaches us that one who teaches another’s children Torah is also deemed to be his/her “father”.

2. When the task appears impossible. As noted above, the census of the Levites demanded Divine assistance. One might ask that since the census was dependent upon Divine revelation, why was there a need for Moshe to do anything at all? Why didn’t G-d simply tell Moshe how many Levites there were? The answer to this question is essentially the formula for man’s actions in this world. An omnipotent G-d could do everything and is hardly in need of human acts to accomplish anything. For reasons known only to G-d, man was placed on this earth with a mission that only he can achieve, and it is his responsibility to fulfill that mission. If the fulfillment of that mission appears to be beyond the scope of man’s capabilities, this does not exempt him from doing his utmost to reach this goal. Man must do whatever he can, and whatever is truly beyond him become G-d’s responsibility. As Pirke Avos states, “it is not up to you to complete the task, yet you are not free to desist form it.” We today, as Moshe then, must not retreat from any mitzvah even if its fulfillment appears beyond our means. We must which we can, and leave the rest to G-d.

3. Impact of Shabbos. “As they rest, so shall they move.” While the literal meaning of this verse is that the tribes of Israel were to travel in the same formation as they camped, this verse also lends itself to another interpretation. Our lives can be divided into: (a) the work week; and (b) Shabbos, the day of rest. Shabbos, the “day of rest” is not merely a day to recuperate from the work week; rather, it is day of spirituality (or, as the Zohar terms it, “the day of the soul”). While oneg Shabbos (enjoying the Shabbos) is indeed a mitzvah and we are required to honor Shabbos with nice clothing and good food, this is not the totality of Shabbos. It is also be a day of “soul,” a day in which we are to utilize its precious moments in prayer, Torah study and other means of connecting to Hashem. If one reflects on the words of the Kiddush — the declaration that G-d created the universe — then one may reflect on the purpose of his/her own existence and dedicate his/herself to achieving that purpose. Used in this manner, Shabbos has the potential to positively impact what we do and how we act even on the weekdays.

Visit the group and request to join.

Visit the group and request to join.