Parsha Bo

A. Summary

i. The 8th Plague (Locusts).

After being warned by Moshe that a plague of locusts would descend upon the Egyptian crops, Pharoh’s courtiers urged him to let the Jewish males leave. However, Moshe and Aharon insisted that all of the Jewish people (and their flocks) be allowed to leave, leading Pharaoh to drive Moshe and Aharon from his presence. The next day, Moshe extended his rod and a swarm of locusts descended, devouring the Egyptian vegetation. After witnessing the plague, Pharoh again admitted his error and begged Moshe and Aharon to make it stop; however, when they complied, Pharoh again became obstinate.

ii. The 9th Plague (Darkness). Moshe then brought the next plague — total darkness — which descended upon the Egyptians for six days (during the last three of which they couldn’t move about). (The Jews, however, were given light in their dwellings.) As the chaos was overwhelming, Pharoh offered to allow all of the Jewish people (but not their flocks, which he intended to hold as a surety for their return) to leave. Moshe refused Pharoh’s stipulation, and Pharoh again drove away Moshe and Aharon from his presence. Moshe warned that there would be one last (and devastating) plague which would kill all Egyptian firstborn, and left for the last time.

iii. The Pesach Offering and Holiday. Hashem informed Moshe that redemption was near and that henchforth the year would begin with the month of their deliverance (Nissan), and that Jews should observe the laws of sanctifying the New Moon (Rosh Chodesh). Hashem commanded that, on the Tenth of Nissan, the head of each household should set aside an unblemished young male lamb, which should be examined for blemishes which would disqualify them as an offering. On the evening of the Fourteenth of Nissan, the lamb was to be sacrificed and some of its blood spread on the door posts of the home symbolizing that its inhabitants were Jewish. That night, the meat of the sacrifice was to be eaten when roasted with unleavened bread and bitter herbs, with any remains to be burnt in the morning. This meal was to be consumed in haste and the Jews were to be ready to begin their journey, for that night Hashem would smite the Egyptian firstborn but spare those homes whose door posts were sprinkled with blood. Hashem further commanded that Pesach (Passover) be observed annually as a permanent reminder of the deliverance from Egypt. Only unleavened bread is to be eaten for seven days, and the first and seventh days of Pesach are to be days of holy assembly on which all work is forbidden. (In addition, it was commanded that the sacrifice of the Pesach offering was to be observed in Israel and its significance explained to future generations.)

iv. The 10th Plague (Death of the Egyptian Firstborn). At midnight, Hashem smote the Egyptian firstborn people and animals. Pharoh and his fellow Egyptians arose in the middle of the night, lamented their loss, and from a position of subjugation asked the Jews to leave Egypt.

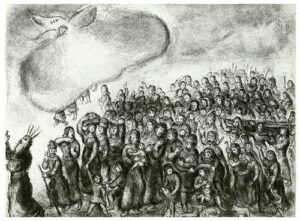

v. The Jews Leave Egypt. The Jews left in such haste that their leavened bread didn’t have time to rise (as a result, we eat Matzos on Pesach). 600,000 adult males, along with their wives and children, left Egypt along with a wealth of gold and silver which the Egyptians had given them. The Jews were commanded to bring a “Korban Pesach” (Pesach offering) every year on the Fourteenth of Nissan; to redeem their first born males in all future generations; and to wear Tefillin “for a sign on your hand and a memorial between your eyes” to remind them of the salvation from Egypt.

B. Divrei Torah

1. LilMode U’Lilamed (Rabbi Mordechai Katz)

a. “Mesiras Nefesh” (Offering One’s Life For Hashem). How did Hashem know that the Jews were worthy of redemption? By asking them to publicly prepare the Pesach offering (i.e., to lead the lamb — which was an Egyptian god — though the streets, slaughter it and spread the blood on their door posts) was to ask them to put their lives in jeopardy. When they complied, Hashem knew that they were ready.

b. True Wealth. Why did Hashem command the Jews to ask the Egyptians for money and jewels as they left Egypt? The Dubno Maggid answers this question with the following parable: A young man was hired by a wealthy merchant, in return for which he was promised a bag of silver coins. At the end of the term, the merchant, extremely grateful for his efforts, gave him a check in an amount much greater than the value of the silver coins; however, the man felt cheated when he received a piece of “paper” in lieu of the coins. When he explained the situation to his father, the father contacted the merchant and explained that since his son didn’t understand the value of a check, he’d appreciate it if the merchant would pay at least some of his wages in silver. In Egypt, the Jews were also too young and inexperienced to fully appreciate the value of receiving the Torah, so Hashem caused them to emerge from slavery with material wealth, thus preventing them from becoming despondent. Only when the Jews grew in wisdom were they able to appreciate the vast richness of the Torah.

2. Artscroll Chumash

a. The Centrality Of The Exodus. Pesach is the inaugural festival of the Jews, as it marks our emergence as a nation. In fact, the Ten Commandments refer to Hashem as “the One Who took Israel out of Egypt” (and not, for example, to “the One Who created the world”). For us, the recognition of Hashem’s Majesty and Mastery and our obligation to serve Him comes from the Exodus, for it was then that we saw His omnipotence and became His people. This is why we observe Pesach as an “eternal decree”.

b. The Meaning Of Tefillin. Ramban teaches that the four passages in the Tefillin — i.e., two passages from this Parsha respecting the Exodus and the first two passages from the Shema — are central to Judaism. The former, which speak of the Exodus, are basic to our awareness of G-d, for it is when we saw that: (a) He liberated us and made us His nation, (b) He showed us that He controls nature, (c) nothing and no one can thwart His will, (d) He communicates through prophets, and (e) He carries out His words at will. The latter express G-d’s Oneness and Kingship, the concept of reward and punishment and the responsibility to observe the Mitzvos. These principles must always be with us — on our arms (i.e., in our actions and opposite our heart which is the seat of emotion) and on our head (i.e., in our intellect and memory).

3. The Chassidic Dimension (the Lubavitcher Rebbe, Rabbi Menachem M. Schneerson, z’tl)

Rosh Chodesh. Why is Rosh Chodesh the first commandment given to the entire Jewish people (and why, parenthetically, was Rosh Chodesh one of only three mitzvos prohibited by the Syrian-Greeks at the time of Chanukah)?:

(1) Mitzvos allow us to permeate the world with goodness and holiness and transform the physical into the holy. Rosh Chodesh sanctifies the first day of the month (and time), by transforming it into a special day, and establishes the entire Jewish calendar (and festivals).

(2) Mitzvos allow us to bring something “novel” into the world. The Hebrew word for month (“chodesh”) is related to the Hebrew word for “novel” or “new”. The novelty was that, through the performance of Torah and mitzvos, the Jewish people can transform the world into a dwelling place for G-d.

(3) Rosh Chodesh symbolizes renewal — the ability of the Jews to rise up from oblivion and restore ourselves; just as the moon disappears at the end of the month, but returns and grows to fullness, so Jews may suffer exile and decline, but are able to renew ourselves (until the coming of moshiach, when we will never be dimmed again).

4. Kol Dodi on the Torah (Rabbi David Feinstein)

a. A Festival For All Jews. And Moshe said to Pharoh “With our youths and our elders shall we go, with our sons and our daughters shall we go, with our flocks and our herds shall we go, because it is Hashem’s festival for us.” It was not enough for only the dignitaries of the Jews to attend the festival; since it was Hashem’s festival, all of the Jews were His guests.

b. True Wealth. Astronomically, the month of Nissan is represented by the constellation “Telleh” (sheep); the Egyptians worshiped sheep as a symbol of wealth. The month of Nissan is also the beginning of spring, the time of new life, when the earth is rejuvenated after a dormant winter. This is the season when people dream of the wealth they hope to realize from their new crops and sheep; as such, it is most important in springtime to denounce the concept that wealth is the primary goal of life. Therefore, the Jews were called upon to worship the sheep, the symbol of wealth.

5. Growth Through Torah (Rabbi Zelig Pliskin)

a. When someone experiences joy don’t say or do anything to decrease it. “And to all the Children of Israel no dog barked [as they left Egypt]”. We should be careful not to diminish someone else’s joy with a pessimistic or deflating comment.

b. Internalize the awareness that Hashem runs the world. R’ Moshe Feinstein, z’tl commented that the month of Tishrei is the month of creation of the world and the month of Nissan is the month of the Exodus from Egypt. Both are lessons in Hashem’s power — the former teaches that Hashem is the Creator of the universe; the latter teaches that Hashem controls the events of the world. By designating Nissan as the “first of the months,” the Torah teaches that the lesson of Hashem controlling world events is the more important of the two. That is, being aware that Hashem created the world may not alter one’s behaviors and attitudes. However, believing that one is under Hashem’s supervision in our daily events leads us to improve our behavior and, moreover, helps free us from worry.

c. You create yourself by your behavior. In response to the question of why the Torah gives a entire list of commandments which were reminders of the Exodus, the Chinuch explains that we influence ourselves and our thoughts by our actions. Even if one is not able to do a certain positive deed (e.g., give charity) with elevated thoughts at first, doing the action will manifest in you the positive traits that you want to integrate. After a while, your actions and thoughts will become consistent.

6. Peninim On The Torah (Rabbi A.L. Scheinbaum)

a. Parents/Teachers Must Also Be Students. “And you shall tell in the ears of your son and your son’s son . . . that you should know that I am Hashem.” The end of the pasuk “and you should know” seems to be inconsistent with the beginning. The purpose of teaching the exile and Exodus to our children is that these fundamental experiences become an integral part of our Nation’s heritage, and a vehicle to embue our children with faith in Hashem. Thus, it should have stated “that they should know.” We can learn from this that the lessons to be derived are not only for the children, but also for the parents. In order for this “course” to be a shared family experience, the parents and teachers must also become the students. (HaRav Yitzchak Aizik Sher, z’tl)

b. Individual responsbility. “And they shall take to them (every man) a lamb for their father’s house, a lamb for a household.” “And they shall slaughter it, the whole assembly of the Congregation of Israel . . . ” In this pasuk, we note this mitzvah in which B’nei Israel are enjoined as they prepare for the Exodus from Egypt focuses upon the head of the household, yet also embraces the entire family and community. Even though there is a great need for collective communal involvement, the individual is not absolved of his personal responsibility. We often become so dependent on communal institutions that we forget what it means to personally fulfill our individual responsbilities. We send the aged to be cared by the communal organizations and the poor to the central Tzedakah funds, and relegate our children to be brought up and taught by others. As B’nei Israel approached freedom and eventual nationhood, they were admonished to bear this idea in mind . . . no nation becomes a nation unless each individual bears his individual responsiblities. Moreshes Moshe also relates this pasuk to one’s parental duties, noting that Moshe could never have imposed his will upon the people without their consent; it was necessary for the entire assembly to be involved. The Rabbi, teacher and school cannot succeed without the parents’ active participation. Lessons in Shabbos, prayer, etc. learned in school can only soak in if they are reinforced at home. Thus, the message from this pasuk is that one must make personal sacrfices at home; one can’t rely on others to do the job. When there is obvious personal sacrficies for Jewish idealism, children grow up consciously aware of their heritage.

7. Wellsprings of Torah (Rabbi Alexander Zusia Friedman)

a. Rosh Hodesh. “This month shall be to you the beginning of months . . . ” The Jewish calendar is built around the moon, not sun. Like the moon, which can shine even thought the darkest night, the Jewish people can survive and spread light even in darkness. (Sfas Emes, z’tl)

b. The Meaning of Pesach. ” . . . and you shall keep it a feast to the L-rd; throughout your generations you shall keep it a feast by an ordinance forever.” If one veiws Pesach merely as the anniversary of liberation from physical oppression and slavery, it would justifiable to argue that there is no sense in celebrating it as long as Jews continue to be exiled and enslaved anywhere inthe world. However, if the Exodus in understood in its proper meaning as the spiritual liberation of our people, in which Hashem led us forth from the corruption of Egypt to take us to Himself as His people and to have His Presence rest upon us so that we became a Holy Nation, then it can be readily seen why Pesach must be observed even while we are still in physical exile and suffering from persecution and oppression. If you celebrate Pesach as a “feast to the L-rd” — as a Divinely commanded feast marking the anniversary of the Jews’ spiritual liberation, then “you shall keep it a feast by an ordinance forever” (i.e., you will be able to observe it always, even during the worst periods of your exile). (Meshekh Hakhmah)

8. Living Each Day (Rabbi Abraham Twerski)

Learning from experience. The Exodus in not merely a historical narration. Everything in Torah is a universal and eternal lesson, to be applied in every age and in every place. The story of the 10 plagues and Pharoh’s reaction to them may seem irrelevant to us today, but it is in fact most relevant. How it that after each plauge Pharoh promised to yield to Moshe’s request to allow the Jews to leave, but no sooner was a plague removed that Pharoh reneged on his promises? When Moshe subsequently warned him of upcoming plagues, Pharoh remained unimpressed until the disaster occurs and then promises only to recant again when the pressure is off. Was Pharoh so ignorant that he was unable to learn from experience? Pharoh’s failure to learn from experience is not uniqure. Many of us fail to do so. Often, we refuse to admit that we were wrong. Self-centered feelings prevent us from learning from painful experiences and thereby avoiding the repetitition of our mistakes. What can we do to overcome this shortcoming? One of the most effective ways is to avail ourselves of a trusted teacher and guide, someone who is unaffected by our emotional distortions and who can help us see reality more clearly and learn from our experiences. As Pirke Avos teaches, “make unto yourself a teacher”.

Next Week: Beshallach

Visit the group and request to join.

Visit the group and request to join.