Parsha Yisro

I. Summary

A. Yisro comes from Midian. While Moshe had carried out his mission in Egypt, his family had returned to Midian. Now that the Jews were in the wilderness, his father-in-law Yisro brought Zipporah and his sons to join him in Rephidim. After Moshe welcomed Yisro affectionately and related what Hashem had done for the Jews, Yisro acknowledged Hashem’s powers and offered sacrifices to Him. Yisro advised Moshe to appoint judges to assist him since he was overburdened with judicial duties, and so that he could focus only on the difficult cases; Moshe did as Yisro suggested. Yisro returned to Midian.

B. Preparations for Receiving Torah. On the first day of Sivan, the Jews arrived in the Sinai wilderness, where they encamped in front of the mountain. Moshe approached the mountain and heard Hashem’s voice instructing him to remind the Jews how He delivered them from Egypt and that, if they obeyed Him, they would be transformed into a “kingdom of priests and a holy nation.” Moshe descended from the mountain and repeated Hashem’s words to the Elders and people, to which the people responded in unison “All that the L-rd has spoken we will do!” Moshe reported these words to Hashem, and was told that Hashem would appear in a thick cloud and speak to him before the entire assembly of Jews (so that His Divine mission would never again be doubted). The people were told to prepare themselves for three days to receive the Torah and not to touch (under penalty of death) the boundaries of the mountain.

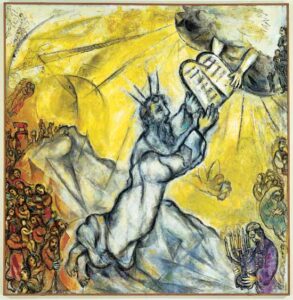

C. The 10 Commandments. On the 6th of Sivan, thunder/lightning erupted and a cloud descended the Mt. The trumpet was heard and Moshe brought the Jews to the Mt.’s foot. The Mt. was enveloped in smoke and Hashem summoned Moshe to its summit. As instructed by Hashem, Moshe told the Jews not to gaze upon His Manifestation. Hashem Himself then declared the foundation of religious/moral conduct, the 10 Commandments:

1. I am the L-rd your G-d who delivered you from Egypt . . . ;

2. You shall have no other gods before Me . . . ;

3. You shall not take the name of the L-rd your G-d in vain . . . ;

4. Remember the Sabbath day to keep it holy . . .;

5. Honor your father and mother . . .;

6. You shall not murder;

7. You shall not commit adultery;

8. You shall not steal;

9. You shall not bear false witness against your neighbor;

10. You shall not covet your neighbor’s house, wife, servant, ox, donkey or any of his possessions.

D. Hashem speaks to the people through Moshe; Moshe begins to receive a series of laws. The people were so awestruck by what they had witnessed that they withdrew (after the second commandment according to Rambam) from the Mt. and pleaded with Moshe to speak to them in Hashem’s place lest they die. Moshe then drew near to the thick darkness and received a series of laws, the first four dealing with Divine worship (i.e., the prohibition against idolatry and general laws respecting the altar).

II. Divrei Torah

A. Lil’Mode U’lilamed (Rabbi Mordechai Katz)

1. A lesson in humility. The Midrash says that when Hashem decided to give the Torah to the Jews, all of the mountains in the desert (except Mt. Sinai) vied for the honor of being the site for this great event. Only Mt. Sinai did not claim itself to be the most fitting site, and for this reason was selected by Hashem. In addition, the Torah was also given in the barren desert, to show that the Torah provides its own glories and doesn’t require the trappings of a fancy exterior in order to be great. Similarly, a person is to be judged on his inner, not exterior, qualities.

2. Free choice or force? When Hashem offered the Jews the Torah, they proclaimed “Na’aseh V’nishma” (“we will observe and then we will hear what the Torah contains”); this suggests that the Jews accepted the Torah of their own accord. Why, then, does the Gemorah state that Hashem threatened the Jews by suspending a mountain over their head until they agreed to accept the Torah? The Midrash teaches that while their acceptance was immediate and enthusiastic, Hashem’s “force” refers to later generations of Jews. Our ancestors were wise enough to perceive the great prize that Hashem offered and we cannot undo their good work by forsaking that gift.

3. Honoring One’s Father and Mother. The 10 commandments are divided into two categories — the first five comprise laws between man and G-d, while the second five relate to laws between man and man. Why, then, is honoring one’s parents in the first five? (A) The Talmud teaches that whoever honors his parents honors Hashem, since it indicates a willingness to accept authority and to carry on the Jewish tradition; (B) Haamek Davar adds that despite one’s natural love [or, G-d forbid, lack thereof] for one’s parents, respect for them is part of one’s obligation to G-d; (C) Respect for parents is a cornerstone of faith in the entire Torah, for our tradition is based upon the chain from Abraham and Sinai, a chain in which the links are successive generations of parents and children (Meshech Chochmah).

B. Growth Through Torah (Rabbi Zelig Pliskin)

1. A parent’s love makes his/her children more loving towards others. The Midrash says that Moshe demanded that the people come to him and thus himself had to walk to the burning bush to come closer to Hashem; the prophet Shmuel, on the other hand, went to the people and thus merited having Hashem come to him. R’ Chaim Shmuelevitz says that this teaches that one’s closeness to Hashem is dependent on one’s love for other people. The Midrash says that Shmuel got his great love for other people from a garment his mother lovingly made for him and which he always kept with him. The love we show our children implants in them a deep feeling of being loved which, in turn, allows them to love others.

2. Love of others, seeing the good in people, and humility are prerequisites to accepting the Torah. “And the Jews encamped’ there near the mountain.” The word “encamped” is in the singular since, as Rashi learns out, they were one unit (“as one person with one heart”). From here, R’ Yeruchem Levovitz notes that love of our fellow man is a prerequisite to accepting the Torah. R’ Yitzchok of Vorki also noted that the word comes from the word meaning “finding favor”; that is, the Jews found favor in the eyes of each other and thus found favor in the eyes of Hashem. Finally, the Nachal Kidumim notes that togetherness is possible only when there is humility which allows you to find good, rather than fault, in others. By growing in these traits, you make yourself into a more elevated person worthy of receiving the Torah.

C. In the Garden of The Torah (the Lubavitcher Rebbe, Rabbi Menachem M. Schneerson, z’tl)

When the Twains meet. Rambam explains that the Torah was given to us not merely to spread Divine light, but to cultivate “peace”. “Peace” refers to harmony between opposites. Chazal teach that the verse “the heavens are the heavens of G-d, but the earth He gave to the children of man” means that originally there was a Divine decree separating the physical from the spiritual; at the time of the giving of the Torah, however, G-d “nullified this decree” and allowed for unity between the two. However, true peace involves more than the mere negation of opposition. The intent is that forces which were previously at odds should recognize a common ground and join together in positive activity, to bring about an awareness of the G-dliness in every element of existence.

D. Wellsprings of Torah (Rabbi Alexander Zusia Friedman)

Remember and Keep the Shabbos. “Remember the Shabbos day to keep it holy.” As Rashi notes, the words “remember” and “keep” were spoken in one utterance. A poor man may find it easy to “keep” the Shabbos since he has no business concerns which demand his attention during the Shabbos, but he may have difficulties “remembering” the Shabbos since he may lack the money to honor the Shabbos by drinking wine, partaking of good food, etc. A wealthy man, on the other hand, may find it simple to “remember” the Shabbos with care since he has more than enough money to buy food and drink with which to do so, but may find himself remiss in “keeping” the Shabbos for fear that he might suffer great financial losses by shutting down his business for a day. Thus, Chazal point out that the two commands — to “remember” and “keep” the Shabbos — were said in one utterance and that therefore no distinction can be made between them. The wealthy man is duty bound not only to “remember” the Shabbos, but to “keep” it as well. At the same time, he must help the poor man to “remember” the Shabbos by providing financial assistance to enable him to “remember” it fittingly. (Dubno Maggid)

E. Peninim on the Torah (Rabbi A.L. Scheinbaum)

1. Reaching out. “And Moshe sent away his father-in-law, and he (Yisro) went his way to his own land.” Rashi comments that Yisro went home solely to convert the remaining members of his family to Judaism. The Maharal interprets the words “and Moshe sent” to imply that Moshe gave his blessing to Yisro’s return. HaRav A.H. Leibovitz extols the supreme sacrifice which Yisro made by leaving B’nai Yisroel to return to Midian. B’nai Yisroel had been privy to an uniquely miraculous existence — sustained by Manna and protected by Hashem’s clouds of glory and a pillar of cloud, they experienced the ultimate spiritual moment. Under the tutelage of Moshe, they shared the consummate environment for unparalleled spiritual growth. Thus, they must have been a good reason for Yisro to withdraw from this environment in order to return to the heathen surroundings of Midian and, furthermore, for Moshe to have blessed his return. HaRav Leibovitz points out that we can learn from Yisro about our obligation to reach out to our alienated brethren. If Yisro was willing to perform this task, how much more are we obligated to reach out to our fellow Jews, even when it causes us to make personal sacrifices. The spiritual and physical well-being of our brethren is a responsibility we must shoulder with love, devotion and pride.

2. Honoring your father and mother. The Exodus from Egypt and the Revelation of the Torah on Mt. Sinai are the two basic focal points in the history of the Jewish people. They constitute the foundation for our submission to Hashem. Although these events are historical truths, the acknowledgment of them is solely dependent upon tradition. Tradition is developed by the loyal transmission by parents to children, and by the children’s’ willing acceptance of these ideals from the hands of their parents. Consequently, the mitzvah of honoring one’s parents has become the basic condition for the continued existence of the Jewish people. Through father and mother, Hashem gives the child not only his/her physical existence, but also the bond which joins the child to his/her Jewish past. The child must receive from his parent the Jewish mission in knowledge, morals and education so that he/she can, in turn, transmit the tradition to his/her children.

F. Living Each Day (Rabbi Abraham Twerski)

Prerequisite to Torah. The receiving of the Torah at Mt. Sinai required three preparatory days. However, except for the requirements of abstinence and the cleansing of garments, no specifics are given as to what was to occur during these three days. Rabbi Yerucham quotes the Talmud that if there is no “derech eretz” (decency, proper behavior), there can no Torah. He states that the three days were for concentration on midos, on developing those character traits which make a person suitable to receive the Torah. Proper midos is a necessary prerequisite to receiving the Torah. The choice of Sinai as the site for the revelation is a powerful lesson in midos, for it teaches us that Torah can only exist in the presence of humility. The opposite of humility — vanity — precludes the development of good midos. Preoccupation with one’s self, considering oneself superior to others, demanding recognition and indulging oneself are all natural consequences of vanity. Only when one realizes that he was put into this world to accomplish a mission — to do the will of Hashem — can he achieve the necessary conviction and self-effacement necessary for the study of Torah and ritual observance.

G. Darash Moshe (Rav Moshe Feinstein, z’tl)

The Mothers’ Role. “So shall you say to the House of Jacob, and relate to the Children of Israel.” On this verse in which Hashem directs Moshe to transmit the Torah to the Jewish People, Rashi comments that the term “House of Jacob” refers to the women, while the “Children of Israel” refers to the men. Why did Hashem tell Moshe to give the Torah first to the women? The Torah can be perpetuated only if each individual and each family takes on the responsibility of transmitting it to their offspring, so that they will in turn keep the mitzvos and pass them on to their offspring after them. This is best acheived by the transmission of Torah at an early age, when an individual’s heart and mind are most receptive. When a child grows up, his/her mindset becomes more fixed and it is much more difficult to inculcate such a fundamental and pervasive value system as the Torah provides. Woman, who provide for the child’s physical needs from the outset, are in the best position to begin the process of the child’s spiritual training at the same time. Thus, Hashem told Moshe to give the Torah to the women first, for they are first to have influence on the future generations, without whom Judaism can not survive.

H. Reb Michel’s Shmuessen (Rabbi Michel Barenbaum)

The Meaning of the commandments. Chazal teach “the commandments were only given for man to become purified through them.” This teaches us that the purpose of commandments is to provide us with a vehicle to spiritual uplifting, to the sanctification of the soul. Thus, it is impossible for one to fulfill all of the mitzvos to the “letter of the law,” yet remain in a low spiritual plane. He may be “full of commandments,” but he is nonetheless empty of spiritual content. Perhaps this is the message of the arrangement of the first two sections of the Shema — i.e., why the Shema is recited before the Vehaya Im Shamo’a. So that a person should first “accept upon himself the Yoke of Heaven, and only then the Yoke of commandments (Berachos 13a).”

I. Majesty of Man (Rabbi A. Henach Leibowitz)

The Chosen People. “And you shall be My treasure amongst the nations, for the entire world is Mine”. Why did Hashem need to remind the Jews that the “entire world is His”? Isn’t that obvious? Rashi explains that this is to remind us that Hashem could shower His affection on so many others rather than us, thereby allowing us to more fully appreciate His love for us. In all of our relationships (e.g., our relationship with Hashem, our spouses, friends, etc.), we must remember that others’ love and kindness is bestowed on us uniquely for us. By so doing, we can more fully appreciate the blessings of these relationships.

J. Artscroll Chumash

1. The Torah commands us to both “remember” (i.e., e.g., make Kiddish, study Torah, set aside special foods to sanctify) and “guard” (e.g., honor the Shabbos by refraining from work and other practices which diminish the sanctity of) the Shabbos.

2. The Torah commands that we must “accomplish all of our work in six days”; even if there is more to be done, we should feel as though everything has been finished (Rashi). Shabbos teaches us that Hashem is the Creator, who provides for His creatures.

3. “Hashem blessed the Shabbos day and sanctified it” —

a. Hashem blessed it with the double portion of manna on Friday, and sanctified it by not giving manna on Shabbos so that no one would be forced to gather it (Rashi).

b. The blessing/sanctification refers to a Jew’s heightened capacity to absorb wisdom and insight on Shabbos (Ibn Ezra).

c. The Shabbos is blessed in that it is the source of blessing for the rest of week, and sanctified because it draws its holiness from higher spiritual spheres (Ramban).

d. The verse suggests that Hashem created the world to last for “six days plus the Shabbos”; Shabbos gives the world the spiritual energy to exist for another week, and the cycle goes continues continuously (Or HaChaim).

4. The 10 Commandments as a blueprint for the entire Torah. The 10 Commandments, while seemingly narrow, have broad ramifications. For example, the prohibition against murder alludes to acts which are tantamount to murder (e.g., causing someone significant embarrassment; failing to provide food and safety to travelers; causing someone to lose his/her livelihood); similarly, the prohibition against theft alludes to acts which are tantamount to theft (e.g., failing to respond to another person’s greeting; winning someone’s gratitude or regard through deceit, etc.)

Next week: Mishpatim

Visit the group and request to join.

Visit the group and request to join.